The Exhibit

Exhibiting Whiteness

Unlike the ideal of Victorian femininity critiqued by Davis, home economics at Cornell did not exclude women of color; or at least, not exactly. Cornell’s Annual Reports show that Indigenous women participated in Cornell winter courses from the early years of the home economics program and also that Black women at Cornell likely took classes in home economics.[1] In 1926, Myra King Hammond, a Black woman, graduated after three years at Cornell from Home Economics. Cornell home economists used Black and Indigenous women both metaphorically and literally to educate all their students about the traditions, fashions, and practices of non-white “others.” However, this exhibition is not about the inclusion or exclusion of Black and Indigenous women from the history of home economics.[2] Inspired by Angela Davis’s critical insights, this analysis of the Standards for a New Womanhood asks about the quiet legacies of racist ideas underlying the emergence of professionalism in the United States, and specifically how home economics at Cornell drew upon these cultural standards to establish this new profession. These legacies are quiet because they often remain unnoticed, and worse have been presented as technical, neutral, and scientific.

In his book Stamped from the Beginning, Ibram X. Kendi describes the treatment of certain Black people as “Black exhibits.” Black exhibits were Black people held up as emblems of success and aspiration. These were exceptional people like Phyllis Wheatley or Frederick Douglas, who achieved greatness in the eyes of their white contemporaries despite their Blackness, as if this were a hardship that needed to be overcome. Black exhibits did not display Blackness, but the traits, values, and achievements that were recognizably “good” within the dominant cultural framework. In other words, they exhibited whiteness. Speaking of these Black people as a kind of “human evidence,” Kendi explains the twisting logic of these human exhibitions: “As trained exotic creatures in the racist circus, Black people could showcase Black capacity for Whiteness, for human equality, for something other than slavery” (94–95). In this exhibition, I will not use Black or Indigenous women to display whiteness.

Instead, this exhibition asks how whiteness has been posed as race-neutral in the cultural construction of professional knowledge, behavior, and appearance. Cherryl Harris has defined whiteness as a kind of property inherited or acquired. Like property and other forms of wealth, then, whiteness is also a kind of cultural capital. As Pierre Bourdieu has argued, cultural capital may be typically "inherited" from one’s family, but it can also be rationalized and transferred through University training. For the purposes of this exhibition, whiteness should be understood as the set of behaviors, postures, and judgements that have been equated with the credibility, value, and status of the professional. As the Black faculty of Columbia University’s GSAPP argue in their 2020 statement “Unlearning Whiteness,” challenging the implicit belief in the superiority of whiteness requires a deep and sustained interrogation of whiteness itself. This exhibition interrogates some of the materials and methods that implicitly championed whiteness on the path toward professional status; and in particular, the ways these new professionals re-fashioned the bodies of rural women throughout New York State between 1900 and 1930. Whiteness is an institutionalized legacy of power, but it rears its head in the practices of sitting, dressing, walking, and even designing.

Agenda

From its inception in 1900, home economics at Cornell provided an early pathway primarily for white women to develop economic and social independence as professionals in a variety of disciplines including nutrition, hygiene, and public health, industrial economics, child psychology, extension work, and design. Building from the RMC online exhibition “What Was Home Economics: from Domesticity to Modernity,” Standards for a New Womanhood interrogates the historical development of this new profession. While many have debated the role of home economics in the progress or regress of feminism as well as the details of its emergence as a new professional discipline, few have acknowledged the centrality of whiteness in its material and intellectual formation. This exhibition draws on the history of Cornell’s College of Home Economics (now the College of Human Ecology) to nuance our understanding of what was at stake in the rise of home economists’ “standards for a new womanhood.” Public recognition of women as “experts” relied on their claim to authoritative knowledge through their “biology” and essential nature. Ultimately, their public recognition as “professionals” required them to employ technical methods designed to exclude their gendered bodies, passions, and personal interests from the services they provided. In each instance, the whiteness of these women was taken for granted. What can we learn from this history of the home economist’s navigation and cultivation of ideals in their search for public recognition? Where might we find quiet but pervasive legacies of racist ideas in our perceptions of professionalism today?

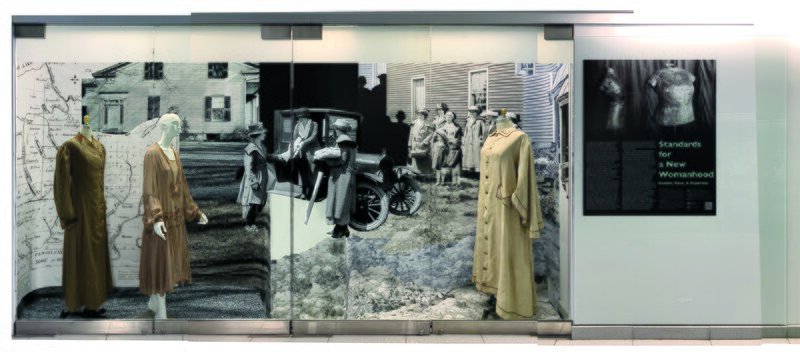

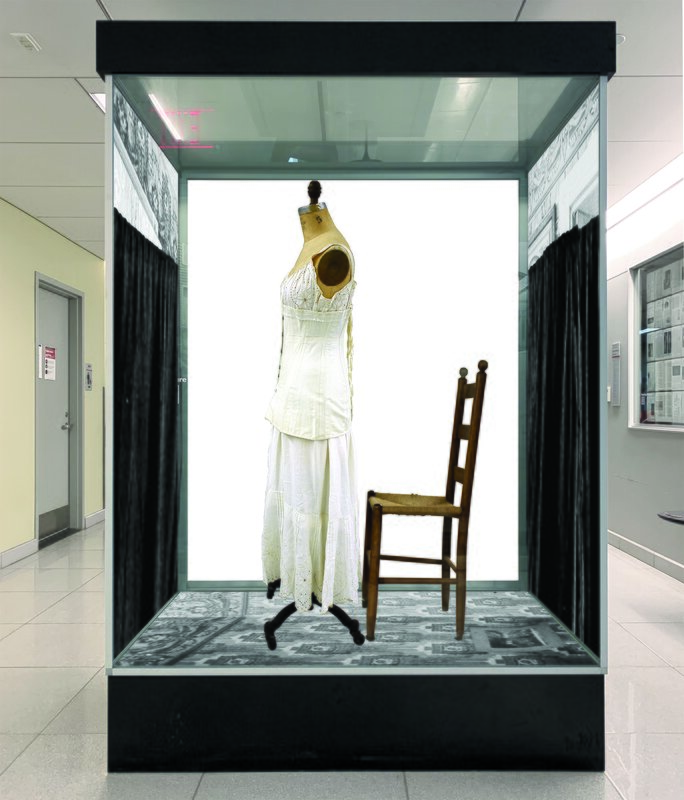

Emblematic of just how invisible these legacies often are, the gummed-tape dress form displays how home economists literally and metaphorically transformed the white bodies of themselves and their clients into supposedly neutral tools. The gummed-tape dress form was an affordable technique for women to make custom dress-forms of their own bodies. It was with clever tools like this that home economists effectively transformed the modern techniques of a turbulent world into a measured and straightforward service for rural farm women.

While white bodies cannot be seen in the gummed-tape dress forms shown in this exhibit, their whiteness can. The social relationships forged in what has been called both the Progressive and Jim Crow eras remain present in the materials, bodies, and practices which made these forms possible. Fashioning one’s body along the lines proscribed by the dominant cultural expectations of whiteness need not (and often does not) look like whiteness. For instance, while this photograph could depict the custom-made dress form of any woman at all, in order for that woman to make her body look like this she would first need to have formed a community, a space, and a schedule according to the instructions laid out by Cornell’s rural bulletins. Simply put, and as many scholars have argued, appearing neutral is the privilege of those who follow the rules. Similarly, asking what professional expertise looks like will not get you as far as acknowledging the visible characteristics that those deemed professionals share in common. This exhibition attempts to materialize a set of displays that consider how fashioning one’s body as a professional may not mean wearing a special uniform as much as it relies upon the standardizations of gendered and racialized behaviors through which one enacts professional expertise.

Extending from Martha van Rensselaer’s first office in the basement of Morrill Hall in 1900, through the first new home economics building (later renamed Comstock Hall and today the CCC Building) starting in 1911, to an emblematic rural farmhouse in Central New York State, this exhibit offers five scenes of professional enactment through fashioned bodies within fabricated spaces. These anecdotes present a circular narrative beginning and ending with Case 5: Reading-Courses displaying a selection of rural bulletins published between 1901 and 1926. Not only a means of distributing knowledge across NYS, these publications were also home economists’ first means of collecting data and forging community ties that made their status as professionals possible. Case 4: Posture materializes an early lesson from these bulletins on the problem of fatigue. A closer look at a popular corset from this moment reveals unexpected cultural and physical tensions between efficiency, posture, and propriety. In Case 3: Dress Forms, you will see the process of constructing a gummed-tape dress form, which allowed rural women to tailor their own garments more efficiently at home. Reliant upon community organizations, as mentioned above, these custom-made forms help reconsider the relationships between industry and bodies famously analyzed by Dr. Lillian Gilbreth and her husband Frank.

Travel between Cornell’s campus and rural farmhouses relied on hard-packed roads, automobiles utilized by the College, and independent train lines. Case 2: Travel portrays a group of home economists arriving for a home demonstration with a variety of supplies, inviting you to consider the means by which these women traveled across NYS. The rural parlor depicted in Case 1: Design offers the spatial context of numerous home demonstrations, study clubs, Home Bureau and early 4H club meetings. With a weekend-long course taking place in the back parlor, here you can see a black curtain raised to teach participants about principles in garment design, one of the many topics that comprise the new discipline of home economics and one of the recurring themes in their many publications. Before unraveling these vignettes any further, however, it is important to understand a bit more of the historical context that set the stage for home economics as a profession; and, in particular, the ways in which it relied upon the intersection of gender, race, and expertise.

[1] Race has not been mentioned in student enrollment numbers in home economics that I have found thus far. However, digital collections do show some student graduation photographs. Most Black women seem to have graduated with an AB rather than an Agriculture degree meaning they were likely enrolled in the University and not the home economics program. (Petrina Jackson (Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections), “RMC Resources: Early Black Women at Cornell.” Online Resource Guide. https://rmc.library.cornell.edu/earlyblackwomen/EBW_Resources.pdf

[2] For those curious what home economics could mean from the perspective of a Black home economist, see Allison B. Horrock’s 2013 lecture on Dr. Flemmie P. Kittrell (Ph.D. 1936), the first Black woman to earn a Ph.D. in home economics. Horrock’s dissertation “challenges historiographical gaps that have made Kittrell not only unknown, but in various ways, unthinkable” in the history of home economics.