Case 4: Posture

“A well-poised woman has greater efficiency and a greater power over others than does one with less poise.”

A well-poised Woman

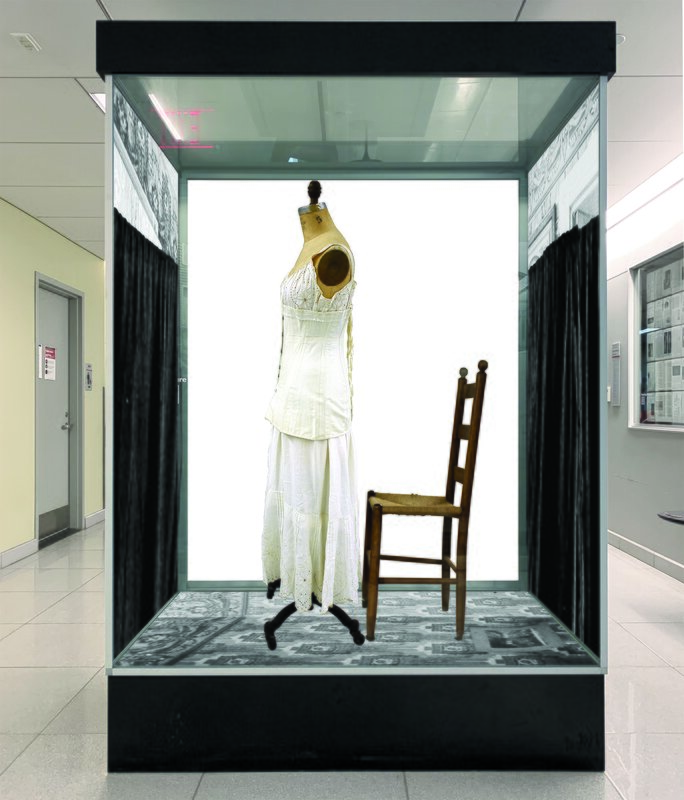

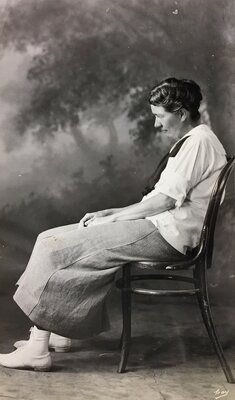

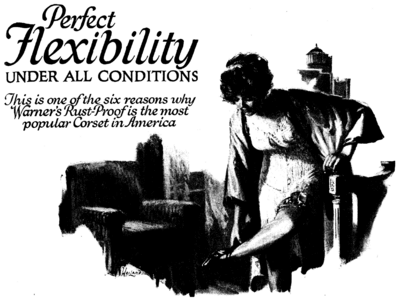

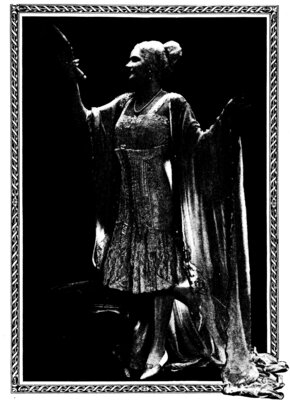

This case presents two photographs of a woman seated in profile on a bent wood Thonet chair before a wistful backdrop. The first image of the didactic pairing displays the woman’s correct, upright posture with her feet squarely set on the ground, hands folded, shoulders lowered, and attentive features. The second presents the same woman slumped down in the chair and perhaps bored. As Kenneth L. Ames explained in the section of his 1992 book titled posture and power, “sitting was only a little piece of a larger phenomenon that we now recognize as subtle and pervasive. But it is from such little pieces that effective ideologies are built” (232). In short, “posture is material culture” (Ames 1992: 186). Case 4: Posture dissects the interdependence of bodily health, mechanical efficiency, and moral aspiration of a well-poised woman. Linked with efficiency, etiquette, and ability, “poise” was a quality that could be recognized in a person’s body and one which designated expertise. It is important to note that slouching like this is only possible when wearing certain undergarments. In other words, if this woman were wearing the kind of corset popular in in the late nineteenth century, she would physically be able to slouch in this way. Whereas, wearing something like the Warner Corset displayed in Case 4, one could let their shoulders hunch forward so long as their hips and lower abdomen could remain relatively in alignment. As you might expect, the ads for corsets in Good Housekeeping in the early 1920s emphasized the importance of increased flexibility. At the same time, however, they also maintained prior notions of elegance. As the Discussion Paper for this bulletin suggested to its readers: “If possible, introduce, from sculpture or pictures, the study of some strong ideal of manly or womanly strength—for example, of Apollo, Venus, or Diana” (242).

Time-motion studies in home economics have largely been discussed as an outgrowth of the “efficiency craze” (Haber 1964; Zunz 1991) and as a re-application in the household of the Taylorist methods developed for the factory (Banta 1993; Alexander 2008). Focus on the mechanics of the body was far more than a question of efficiency, however, and drew up existing conceptualizations of how a body ought to look and move under different circumstances and even with certain identities. The managerial role of body efficiency rhetoric was undergirded with moral assumptions held over from the end of the nineteenth century. Victorian notions of propriety and social bearing remained significant but had been transformed in both overall look and application through a concentrated focus on the body that would have itself been deemed obscene thirty years earlier.

This example implies more than the value of increased female efficiency as any etiquette manual of the era would likely confirm. While good posture projected strong character, bad posture not only strained one’s neck and back, it also projected impropriety and potential degeneracy. In the 1920s, words like degeneracy and decadence carried a particularly loaded connotation linking interwar excesses with a newly empowered racial stereotyping (Hartman 2019). The correlation between bodily health, mental state, and the ideological value of certain postures comes across clearly in an excerpt from “Saving Strength”:

"Depressed mental states have an involuntary restrictive effect on all the vital processes. To be blue or sad or despondent is to have the breathing, the circulation, and the innervation of the body less than normal—the latter to such an extent that not enough nervous energy is sent to the muscles to give them tone and vigor. The results are that the muscles become unduly relaxed, the chest sinks, the head droops, and the feet and legs drag. One must summon to the will to the res[c]ue. The inert muscles and heavy body must be energized and invigorated. The very effort made in thus taking oneself in hand and holding the body bravely erect, affects the mental state wholesomely. Courage begins to replace despondency. […] Everyone admires a woman who is reposeful. A well-poised woman has greater efficiency and a greater power over others than does one with less poise."

The correct and incorrect postures depicted in the 1903 edition of “Saving Strength” differ from those published in 1920. While the “incorrect” posture has changed between 1903 and 1920, the “correct” posture has not.