Section III - (A)dressing Class and Culture

The Fashion – Tradition Collision

By Esuvat Bomani

This is a kitenge dress from Arusha, in the Northern region of Tanzania. The fabric is thick and colorful and a marker of class for women in the country. The kitenge itself is likely sourced from a factory in Tanzania or in Kenya due to the vibrant colors and designs that are more commonly used in coastal areas. This dress is significant as it represents the constant ‘updates’ that can occur to traditional dress. The kitenge historically was used as an official cloth for women with conservative styling and due to its rarity. Before the kitenge, Kanga was the most popular fabric. It was lighter and included sayings that could be anything from religious quotes to quips to ridicule others with flare. Kitenge was therefore also a marker of class as the fabric was more timeless (due to no sayings that could go out of style) and more durable due to its thickness. The kitenge has acted as a social barometer and a means to mark class as well as to create an identity. The identity communicated from this dress is one that is ‘cosmopolitan’ in nature. The dress is not long, and it is sleeveless. This is a more western kind of style. At the same time, due to the elastic on the dress, it could easily be converted to a skirt, which in that case would appeal for more conservative fashion.

This dress is from Dar-es-salaam, Tanzania. It is commonly referred to as a ‘Dera’ or ‘Deera’ and has thin Kanga-like fabric. The Dera entered Tanzanian markets through import from India and is a design that originated from the coast of Somalia. It is a long, free-form dress that is practical in its use for warm coastal regions. It is a dress that one would use for casual day to day wear and for working. The dresses are cheap as they do not require alterations or sizing from tailors and the style allows for much needed ventilation in the warm coastal region. This item is not one linked with ‘fashion’ due to the lack of modern or western influence. The women who choose to wear Deras and want to communicate status would do so by accessorizing, but the dress itself is accessible to all people and even the more ‘expensive’ Dera’s are cheaper than the cheapest Kitenge items.

Significance and Use of Pagnes

By Laure-Emmanuelle Dalle

During traditional Cameroonian wedding ceremonies, each side of the family is expected to wear their own distinct print, for the first half of the ceremony. The items worn in this image were all made of pagne, an uncut printed cotton textile that is typically two yards wide and six yards long. Pagnes are worn around the waist and historically have been used by both men and women. Since the mid-1960s, pagnes have been produced in Cameroon. These locally made cloths are significantly less expensive than imported Dutch wax prints. Moreover, they promote national identity and help support the local textile industry. In this instance pagnes were used to create wedding ceremony attire, but they are used for casual dress as well by both men and women.

A Cross of Tradition and Cultural Wear: Malian Women Fashion

By Bintou Sow

Fatoumata is wearing a traditional dress from Mali, called the bazin. The women’s bazin includes a tunic, a long skirt and a head wrap, musoro. The men’s bazin include a long tunic with pants. The bazin is worn on special occasions like weddings, birthdays, and importantly, eid celebrations. Eid al fitr specifically is the muslim holiday after the end of the holy month, Ramadan, month of fasting. The bazin reflects the modesty expected of men and women in this predominantly Muslim country. The components of the bazin are standard, however, wearers personalize their bazin through different accessories. Both men and women will add elaborately embroidered designs to the neckline and hem. Women will also add sequins and jewels to their bazin and augment their look with gold jewelry. Tailors play an important role in designing bazins. Customers share their ideas and desires with their tailor who then creates a unique bazin for each customer.

Kanga: Proverbial Textile

By Kellian Kelly

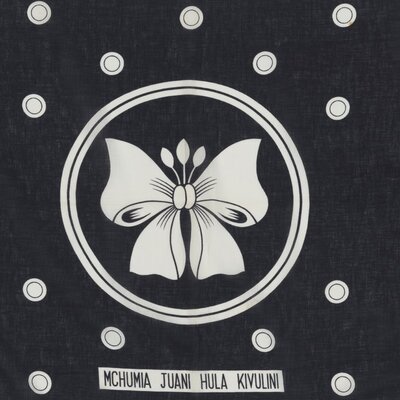

The image is of a kanga that was made in Zanzibar. Printed on it is “MCHUMIA JUANI HULA KIVULINI” The design is registered for Kassamali Dharamsi & Son which was founded by an Indian businessman.

Kangas are a wrap cloth, used mainly by women, from the East African coast. Printed on these kangas are proverbial texts that serve as a non-verbal means of communication. The messages of the kangas were conveyed either by wearing it in the presence of others or by gifting it to someone. The messages that the kanga usually conveys are those that were culturally seen as inappropriate to speak on openly.

The popularity of kangas can be attributed to the abolition of slavery in Zanzibar in 1897. Former slaves began to adopt new means of fashion to integrate into Muslim Swahili society. Kangas were produced by merchants seeking to capitalize off this new interest in fashion post slavery. Merchants in Zanzibar were often Indian immigrants who acted as mediators between the consumers and overseas textile producers.

Let's have coffee!

By Harmela Anteneh

Let’s have coffee! discusses the centrality of coffee in Ethiopian social life and the unique dress culture that is associated with Ethiopia’s elaborate coffee rituals.

This women’s garment is an example of 'habesha libs’ (traditional Ethiopian clothes). Dresses of this kind can be found in both similar and different variations all across the country. This particular piece is more associated with the Gondar region of Northern Ethiopia. While most other traditional clothes in Ethiopia are made of the same cotton fabric material, they are often made to be thin and veil-like. This dress is recognizably thicker than a traditional Ethiopian dress, which is indicative of its Gonderian origins. The cloth is heavy, and is locally referred to as ‘gabi’ (directly translated: blanket) cloth, because it is made with a similar thickness to that of a traditional Ethiopian blanket.

The cloth is made of cotton that is locally grown and spun using small, wooden, handheld spindles. This cotton is woven by weavers who are predominantly male, but are increasingly including females (particularly in urban areas). These weavers use a traditional cotton weaving loom that is made mostly of wood. The designs and patterns are also made of cotton threads that are dyed different colors. They are not embroidered. All the designs are incorporated into the dress as it is being woven on the loom. These dresses are significant to both the weavers who work on the handlooms as well as the workers who do the spinning and winding of the thread, as it provides them with a means of livelihood.

As for consumers, these designs communicate cultural and religious pride. Many dresses, including this one, incorporate crosses into the design. This particular variation, however, is specifically tied to Ethiopia’s traditional coffee ceremony, and is locally known as ‘buna libs’ (directly translated: coffee clothes). Buna Libs is recognizable by the crosses that hang around the shoulders of the dress, the placement and thickness of the colored pattern (or ‘tilet”) that runs down the middle of the dress, and the thickness of the ‘gabi’ cloth itself. You may also notice that the pattern has arrow shaped lines and triangles within it, which is also indicative of its Gondarian origin. Ethiopia’s unique coffee traditions are an integral part of her social customs, and each element of the ceremony, including this dress, is special and significant.

Wrapped in Blue

by Riley Martin

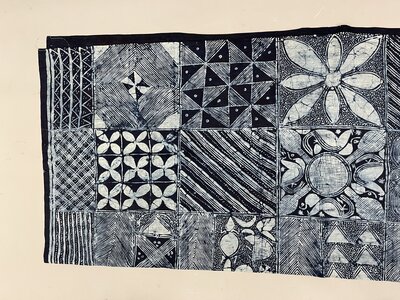

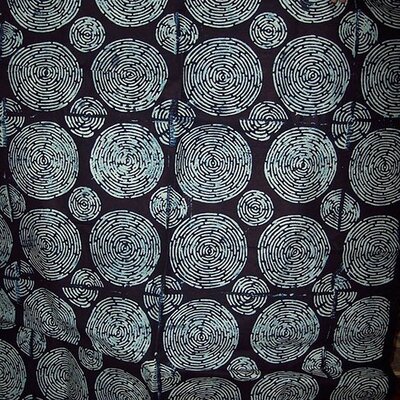

Adire is an indigo dyed cotton cloth produced in the Yoruba region of south-western Nigeria. The cloth is machine woven and two pieces are sewn together to make a larger square piece. The cloth is primarily dyed by women using a variety of resist techniques such as tying, embroidery, stencils and paste, and hot wax to create designs (Wolff). Designs are inspired by nature, religion, philosophy, everyday life and notable events. Finished Adire is typically worn by both men and women, but is more popular as a wrapper dress for women.

Indigo dying has been done for centuries in this region but the importation of cheap machine woven cotton as a product of colonialism created immense growth in adire production and allowed dyers the freedom to make smaller more intricate designs on the smoother surfaces. As industrialization has increased, men have taken over more aspects of production and new synthetic dyes and mordants are sometimes used instead of the traditional indigo (Byfield 91). For a quick overview of the process check out The Centenary Project’s: Wax method of designing on adire (The Centenary Project).