Photography

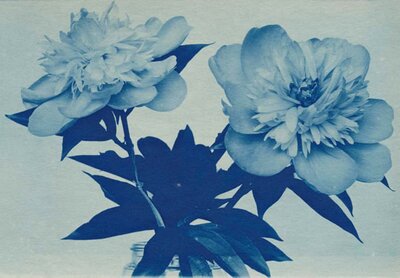

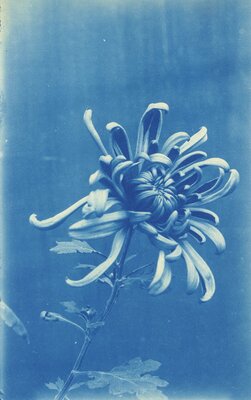

When Liberty Hyde Bailey learned to use a camera in 1886, he did so not as a dilettante, but as a committed photographer. Although he continued to develop his photographic skills throughout his life, his primary goal was not to create outstanding images, but to document horticulture. Nevertheless, Bailey’s photographs-thousands of which have been preserved-testify to his innate aesthetic sense. Many of the images are simply works of art. In recent years, his photographs have been displayed in museums of art, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

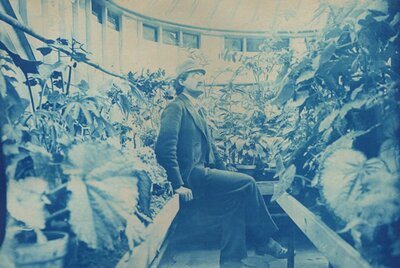

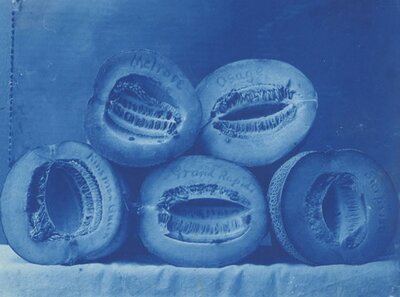

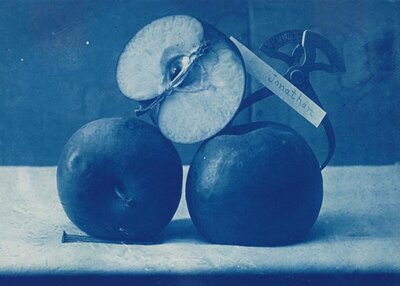

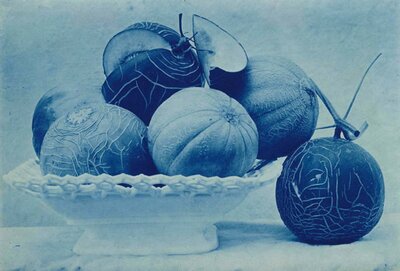

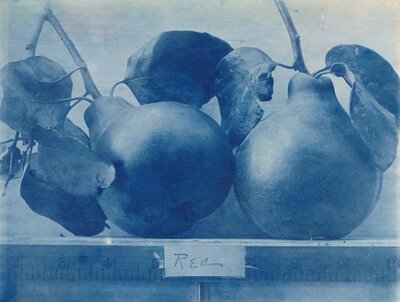

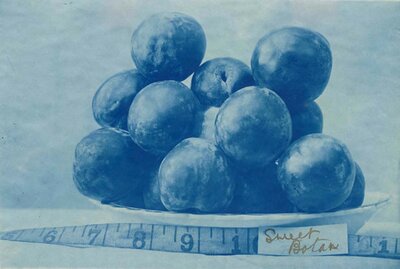

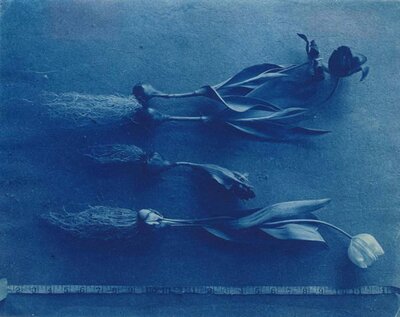

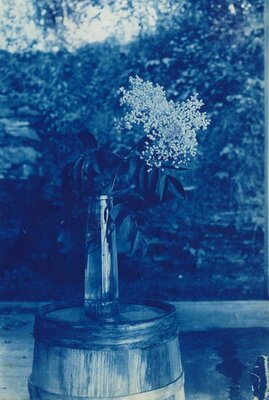

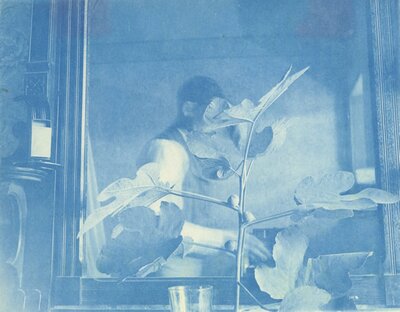

In general, Bailey’s approach to photography was measured and stately. He eschewed the snapshot for the carefully staged still life. His camera was not a handheld tourist’s device, but a large, heavy field camera, which required a tripod and long exposures. It accompanied him to greenhouses and farms just as it did on his trips to exotic destinations. In contrast, Bailey preferred to print his negatives as cyanotypes, in the quickest, simplest process available to him. He carefully numbered, collected and annotated the cyanotype prints in twenty-four albums, which he created between 1888 and 1910. Bailey’s images convey the pure beauty of the flora he cultivated, yet the timelessness and simplicity of his compositions resemble Italian Renaissance still life paintings more than they do horticultural studies.

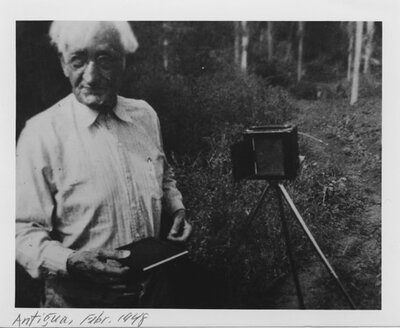

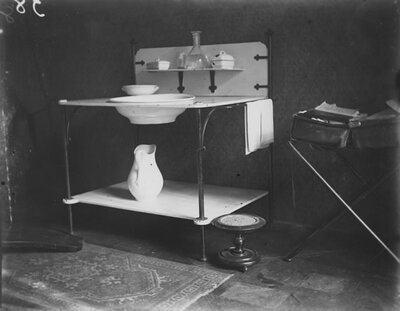

Liberty Hyde Bailey’s Camera

Bailey’s 8 x 10 field camera is hefty. Although it is portable, Bailey had to mount it on a tripod to keep it steady during its long exposures. Bailey continued to use his venerable camera throughout his long life, despite the invention of smaller, handheld models.

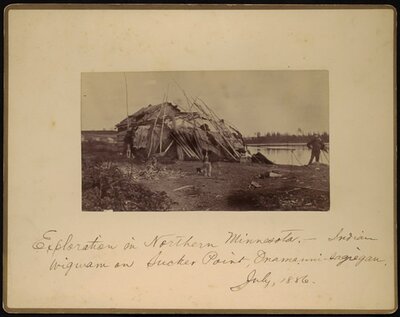

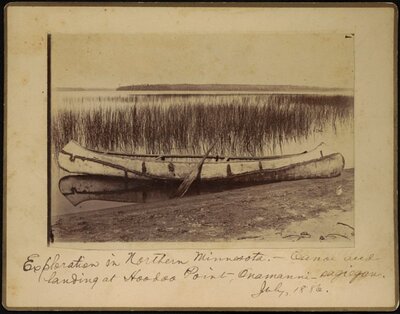

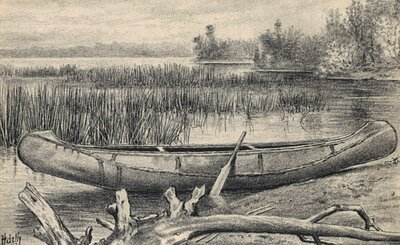

Minnesota

During the summer of 1886, while he was teaching at the Michigan Agricultural College, Bailey took part in a geological and botanical survey of northeastern Minnesota. During that trip, he made some of his first photographs-not of botanical specimens, but of Native American settlements.

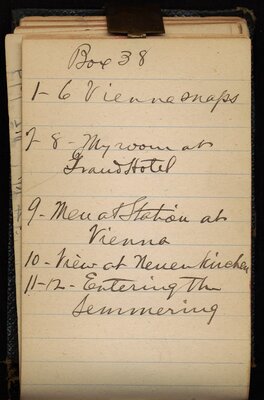

Vienna

In August of 1888, Liberty Hyde Bailey and his family traveled to Europe on their first trip abroad. While in Germany (at that time a leader in the photographic industry), Bailey began to recognize the possibilities of using photography in his horticultural record-keeping. He photographed extensively during the six-month voyage, learning how best to expose glass plate negatives to a variety of lighting conditions. Bailey had substantially mastered the art by the time he returned to the United States in early 1889 to begin a new life at Cornell.

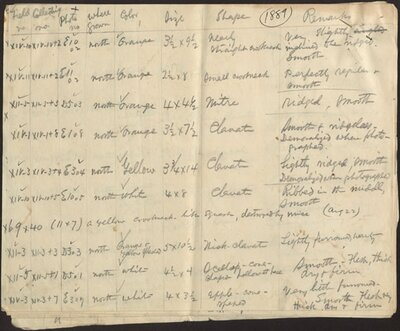

Record of negatives

Even as a beginning photographer, Bailey began recording each negative he made.

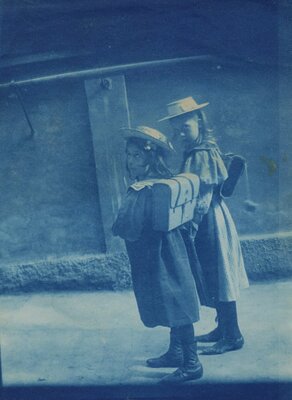

Ethel and Sal

In this rare candid photograph, Bailey captured the excitement of his two young daughters, who, like their father, were becoming avid travelers.

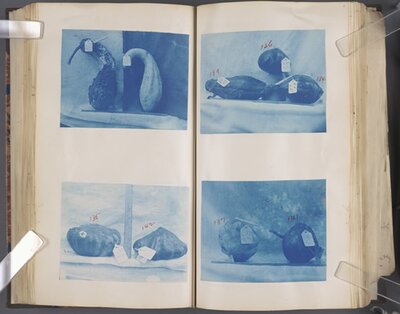

The Pumpkins of 1889

One of Bailey’s first albums of cyanotype photographs. In this case, the images depict his horticultural experiments with pumpkins.

Self-portrait

Bailey occasionally photographed his colleagues, particularly when they were gathered into a discrete group, but he only almost never made self-portraits.

Cyanotypes

Bailey’s favorite method of printing glass plate negatives was to make cyanotype prints. While he sent his negatives to a professional photographer to develop, he usually made his own prints. Cyanotypes require only the use of natural sunlight for exposures and plain water for development. This simple procedure appealed to photographers like Bailey, who produced many thousands of negatives. Indeed, it became the most popular print process for amateurs between about 1880 and 1910, when Bailey was most active photographically. Bailey also discovered that cyanotypes were easy to collect and paste into albums.