Nabokov's Blues

With little formal scientific training, Vladimir Nabokov nonetheless became a very serious lepidopterist, excelling both as an avid collector and a taxonomist. His particular area of expertise became the complex subfamily of Polyommatinae, more commonly known as "the Blues".

Most of Nabokov's scientific achievements took place during his time as de-facto Curator of Lepidoptera in Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ) from late 1941 to 1948. There he often spent up to fourteen hours a day in the lab, expressing that he had permanently ruined his vision from the strain of peering through the microscope for so long. Nabokov loved this work however, noting in Speak, Memory (1951) that “[i]ncredibly happy memories, quite comparable, in fact, to those of my Russian boyhood, are associated with my research work at the MCZ”. It was during his time at the MCZ that Nabokov grew to become a particular authority on Polyommatus butterflies. The scientific papers he published during the 1940’s, have had a fundamental and lasting impact on the field.

Having studied hundreds of specimens of Blues in the MCZ, Nabokov found that the American Blues were in taxonomic disarray and set about reordering them. His 1945 paper, Notes on Neotropical Plebejinæ (in Psyche: A Journal of Entomology) is arguably his most significant scientific paper. In it Nabokov classified an array of South American Blue butterflies, producing the largest crop of new generic names of all his papers and successfully recognizing ten of the eleven now-known genera of American Blues. Of these eleven, five still bear the names Nabokov gave them back in 1945: Paralycaeides, Cyclargus, Pseudolucia, Pseudochrysops, and Echinargus.

The Taxonomist’s Theory

What was even more significant than the classifications in Notes on Neotropical Plebejinæ was the interesting conundrum about the migration and evolution of the American Blues, and the theory Nabokov developed to answer it.

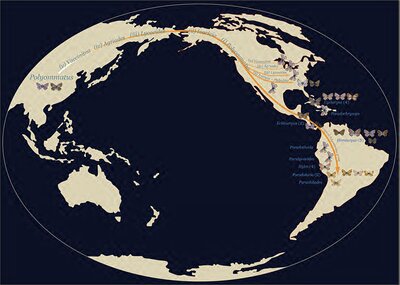

The conundrum was that while all the American Blues seemed to have arrived from Asia via the Bering land bridge, some of the South American Blues seem to have somehow been in place earlier than those in North America. The paper then ventured to lay out a theory of how this might have happened in a series of five distinct and sequenced waves of migration, or an evolutionary timeline. Evolutionary theorizing is generally an endeavor that few taxonomists undertake. Nabokov's hypothesis of waves of migration to explain the geographic distributions and genealogical lineages of all the American Polyommatus Blues is illustrated on the map below.

In this paper Nabokov wrote:

“a modern taxonomist straddling a Wellsian time machine with the purpose of exploring the Cenozoic era would encounter the following series of events in the evolution of these butterflies:

(i) From Asian ancestors, a first colonization event of the New World across the Bering Strait, followed by dispersal southwards to South America. This first stock would produce the current Neotropical taxa, but would subsequently vanish almost completely from North America.

(ii) A second crossing of the Bering Strait made by the ancestors of the Icaricia – Plebulina clade.

(iii) Lycaeides

(iv) Agriades

(v) Vaccinia (explicitly in that order) from Asia to North America following the same route."

Theory Revisited

In 1945 there was no way of verifying these evolutionary speculations, and very few contemporary scientists took Nabokov’s theories seriously. In the 1990’s however, entomologist Kurt Johnson and journalist Steven L. Coates, revisited Nabokov’s work on the Polyommatus, authoring Nabokov’s Blues (McGraw-Hill Professional, 1999) which highlighted the 1945 paper. Reading this book, Naomi E. Pierce, Professor of Biology at Harvard and Curator of Lepidoptera in the MCZ (the same position held by Nabokov when he published this theory) was inspired to test the validity of his hypothesis with the help of modern technologies. Pierce and her international team, including Kurt Johnson, spent a decade collecting and analyzing samples of American Blues, sequencing the butterflies’ genes and analyzing DNA to estimate the genetic distances between the groups involved, as well as the time period when they evolved.

Theory Validated

Their resulting 2011 paper, Phylogeny and palaeoecology of Polyommatus blue butterflies show Beringia was a climate-regulated gateway to the New World, proved that the American Polyommatus Blues are indeed descended from different ancestors, and that their introduction in the Americas was the result of a series of migrations.

Spectacularly, Pierce and her team discovered that not only did Nabokov get the general migratory patterns of the Polyommatinae butterflies across the Bering Land Bridge correct, he also correctly identified the exact order of their movements. They had indeed all originated in Asia and traveled to North America via the Bering Strait, but arrived in the Americas over the course of five separate waves. This first wave consisted of what are now the South American species, which then disappeared almost completely from North America where they were replaced first by Icaricia then three more waves consisting of Lycaeides, Agriades and Vaccinia in that order, exactly as Nabokov had hypothesized.

The study also showed that the land surrounding the Bering Strait was relatively warm ten million years ago when the first wave passed through, and as it chilled steadily ever since, the lineages that came later were increasingly cold-hardy to match the falling temperature ranges. In this 2011 paper, lead author Roger Vila, Pierce’s postdoctoral researcher, states:

"Although sometimes described as an amateur, Nabokov was a serious taxonomist who made important contributions to the systematics of the Polyommatus section and revised many of the New World taxa, particularly in the genus Lycaeides... Our results show that Nabokov’s inferences based on morphological characters (primarily of the male genitalia) were uncannily correct in delineating not only species relationships but also the historical ordering of these five key events in the evolution of New World blues."

Polyommatus Blues

Blues are small butterflies, but many are brightly colored and charismatic. These tiny creatures are also found throughout an enormous range including Eurasia, Northern Africa, and the Americas.

Systematizing and reclassifying the Polyommatus was a remarkable feat, as was developing a theory of their migration and evolution, and Nabokov’s greatest achievements in his work on butterflies in general can be found in the three principal papers he wrote on the Blues. His 1943 paper, "The Nearctic forms of Lycæides Hübner" introduced his systematics, while the 1945 paper "Notes on Neotropical Plebejinæ" delved into morphology and evolution, and the 1949 paper "The Nearctic members of the genus Lycaeides Hübner" amounted to a complete revision of the North American members of the genus.

The Color of Blues

Many of the Polyommatus Blues are vibrantly colored, sometimes with a metallic-blue gloss to their wings. This is the result not of a pigment but to the micro-structure of the wings themselves.

The wings of butterflies and moths are covered by a layer of scales that overlap like roof tiles. Precise spacing of fine ridges on the scales makes them reflect certain wavelengths of light. In the case of what we observe as a blue butterfly it is blue wavelengths of the visual spectrum that are reflected. This is known as structural color.

Iridescent wings are not only beautiful to human eyes, but they can also help aid in survival. The undulating flight pattern of butterflies alone can make them hard to catch, but when the upper surface of the wings continually changes in visible color it can also make them seem to appear and disappear, helping them to successfully elude a predator.

While obviously best known for the beautiful blues of primarily the male’s top side wings, the undersides of butterflies in this subfamily are generally pale browns with dark spots and sometimes splashes of orange and blue.

Relationship with Ants

Many Blues have an interesting and close association with ants. In these species the larvae have a specialized "honey gland", which exudes a sweet cocktail of sugar and sometimes amino acids which attract and feed the ants. While it isn’t entirely understood how the ants benefit the butterflies, it is assumed that attracting the ants provides the larvae some protection from predators or parasites. In some cases ants even accompany adult butterflies during their emergence from the pupa. One example of a Blue butterfly that enjoys a relationship with ants is Nabokov’s Blue.

Nabokov's Blue: Plebejus idas nabokovi (Masters 1972)

First recognized as a distinct taxon by Nabokov from specimens sent to him by Louis Griewisch, who was the first to report the butterfly in Wisconsin, Nabokov's Blue is very similar to its close relatives the Karner Blue and the Melissa Blue. In 1972 Plebejus idas nabokovi was named as a distinct subspecies, and named to honor Nabokov.

Nabokov’s Blue occurs in the Great Lakes Region, where it is distinguished ecologically by its exclusive larval host plant the Dwarf Bilberry (Vaccinium uliginosum) which, like the butterfly itself, is uncommon in the Lake States.

Much like the Karner Blue, Nabokov's Blue is vulnerable due to its dependence on a single host plant, and it was listed as a special concern species in Minnesota in 1996.

The larvae of Nabokov’s Blue produce a secretion that attracts ants, and probably produce a mimic of ant pheromones as well, something which has been documented in other lycaenid butterflies. While the larvae will develop normally even without the help of ants, they likely provide the larvae some protection from predators and parasites.